Recursion is magic, but it suffers from the most awkward introduction in

programming books. They’ll show you a recursive factorial implementation, then

warn you that while it sort of works it’s terribly slow and might crash due to

stack overflows. “You could always dry your hair by sticking your head

into the microwave, but watch out for intracranial pressure and head explosions.

Or you can use a towel.” No wonder people are suspicious of it. Which is too

bad, because recursion is the single most powerful idea in algorithms.

Let’s take a look at the classic recursive factorial:

1 |

|

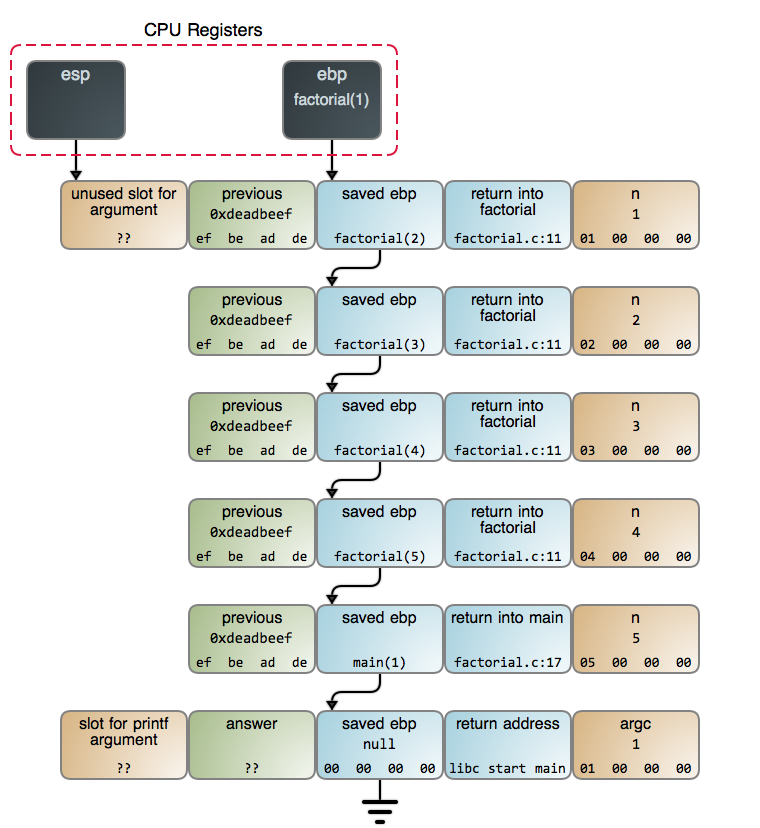

The idea of a function calling itself is mystifying at first. To make it

concrete, here is exactly what is on the stack when

factorial(5) is called and reaches n == 1:

Each call to factorial generates a new stack frame. The creation and

destruction of these stack frames is what makes the recursive

factorial slower than its iterative counterpart. The accumulation of these

frames before the calls start returning is what can potentially exhaust stack

space and crash your program.

These concerns are often theoretical. For example, the stack frames for

factorial take 16 bytes each (this can vary depending on stack alignment and

other factors). If you are running a modern x86 Linux kernel on a computer, you

normally have 8 megabytes of stack space, so factorial could handle n up to

~512,000. This is a monstrously large result that takes

8,971,833 bits to represent, so stack space is the least of our problems: a puny

integer – even a 64-bit one – will overflow tens of thousands of times over

before we run out of stack space.

We’ll look at CPU usage in a moment, but for now let’s take a step back from the

bits and bytes and look at recursion as a general technique. Our factorial

algorithm boils down to pushing integers N, N-1, … 1 onto a stack, then

multiplying them in reverse order. The fact we’re using the program’s call stack

to do this is an implementation detail: we could allocate a stack on the heap

and use that instead. While the call stack does have special properties, it’s

just another data structure at your disposal. I hope the diagram makes that

clear.

Once you see the call stack as a data structure, something else becomes clear:

piling up all those integers to multiply them afterwards is one dumbass idea.

That is the real lameness of this implementation: it’s using a screwdriver to

hammer a nail. It’s far more sensible to use an iterative process to calculate

factorials.

But there are plenty of screws out there, so let’s pick one. There is

a traditional interview question where you’re given a mouse in a maze, and you

must help the mouse search for cheese. Suppose the mouse can turn either left

or right in the maze. How would you model and solve this problem?

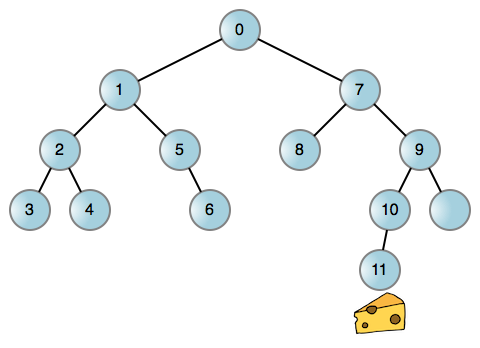

Like most problems in life, you can reduce this rodent quest to a graph, in

particular a binary tree where the nodes represent positions in the maze.

You could then have the mouse attempt left turns whenever possible, and

backtrack to turn right when it reaches a dead end. Here’s the mouse walk in an

example maze:

Each edge (line) is a left or right turn taking our mouse to a new position. If

either turn is blocked, the corresponding edge does not exist. Now we’re

talking! This process is inherently recursive whether you use the call stack

or another data structure. But using the call stack is just so easy:

1 |

|

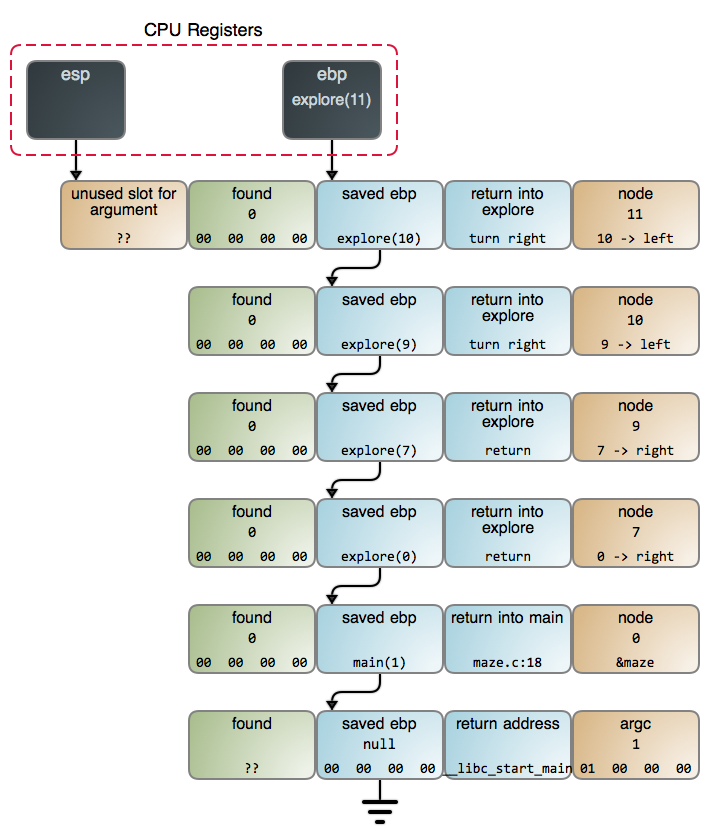

Below is the stack when we find the cheese in maze.c:13. You can also

see the detailed GDB output and commands

used to gather data.

This shows recursion in a much better light because it’s a suitable problem. And

that’s no oddity: when it comes to algorithms, recursion is the rule, not the

exception. It comes up when we search, when we traverse trees and other data

structures, when we parse, when we sort: it’s everywhere. You know how pi

or e come up in math all the time because they’re in the foundations of the

universe? Recursion is like that: it’s in the fabric of computation.

Steven Skienna’s excellent Algorithm Design Manual is a great place to

see that in action as he works through his “war stories” and shows the reasoning

behind algorithmic solutions to real-world problems. It’s the best resource

I know of to develop your intuition for algorithms. Another good read is

McCarthy’s original paper on LISP. Recursion is both in its title

and in the foundations of the language. The paper is readable and fun, it’s

always a pleasure to see a master at work.

Back to the maze. While it’s hard to get away from recursion here, it doesn’t

mean it must be done via the call stack. You could for example use a string like

RRLL to keep track of the turns, and rely on the string to decide on the

mouse’s next move. Or you can allocate something else to record the state of the

cheese hunt. You’d still be implementing a recursive process, but rolling your

own data structure.

That’s likely to be more complex because the call stack fits like a glove.

Each stack frame records not only the current node, but also the state of

computation in that node (in this case, whether we’ve taken only the left, or

are already attempting the right). Hence the code becomes trivial. Yet we

sometimes give up this sweetness for fear of overflows and hopes of performance.

That can be foolish.

As we’ve seen, the stack is large and frequently other constraints kick

in before stack space does. One can also check the problem size and ensure it

can be handled safely. The CPU worry is instilled chiefly by two widespread

pathological examples: the dumb factorial and the hideous O(2n)

recursive Fibonacci without memoization. These are not indicative of

sane stack-recursive algorithms.

The reality is that stack operations are fast. Often the offsets to data are

known exactly, the stack is hot in the caches, and there are dedicated

instructions to get things done. Meanwhile, there is substantial overhead

involved in using your own heap-allocated data structures. It’s not uncommon to

see people write something that ends up more complex and less performant than

call-stack recursion. Finally, modern CPUs are pretty good

and often not the bottleneck. Be careful about sacrificing simplicity and as

always with performance, measure.

The next post is the last in this stack series, and we’ll look at Tail Calls,

Closures, and Other Fauna. Then it’ll be time to visit our old friend, the Linux

kernel. Thanks for reading!